A deep dive into AI-powered document processing

The origin story

ZapDoc is an AI-powered document processing platform that extracts structured data from PDF documents and delivers results in Excel format via email.

I didn’t start out wanting to build a document automation platform.

What I wanted was leverage. I’d seen firsthand how time-consuming and painful it was to pull structured data out of messy PDFs: invoices, CVs, contracts, proposals… all needing to be manually parsed, copy-pasted, or hand-entered into Excel.

So I asked myself: Could I build something that turns these documents into clean, structured spreadsheets, with zero effort from the user?

After a few weekends and sleepless nights, the answer became ZapDoc, a web tool that:

- Takes multiple PDFs or a .zip archive,

- Lets you define which fields you want to extract (e.g. “name”, “email”, “amount”, “date”),

- And returns a clean Excel file by email.

It sounds simple, but the devil is in the details.

From MVP to modular system

I built the first prototype over a weekend: FastAPI for the backend, hosted on Railway; a minimal React frontend on Vercel; and OpenAI for field extraction.

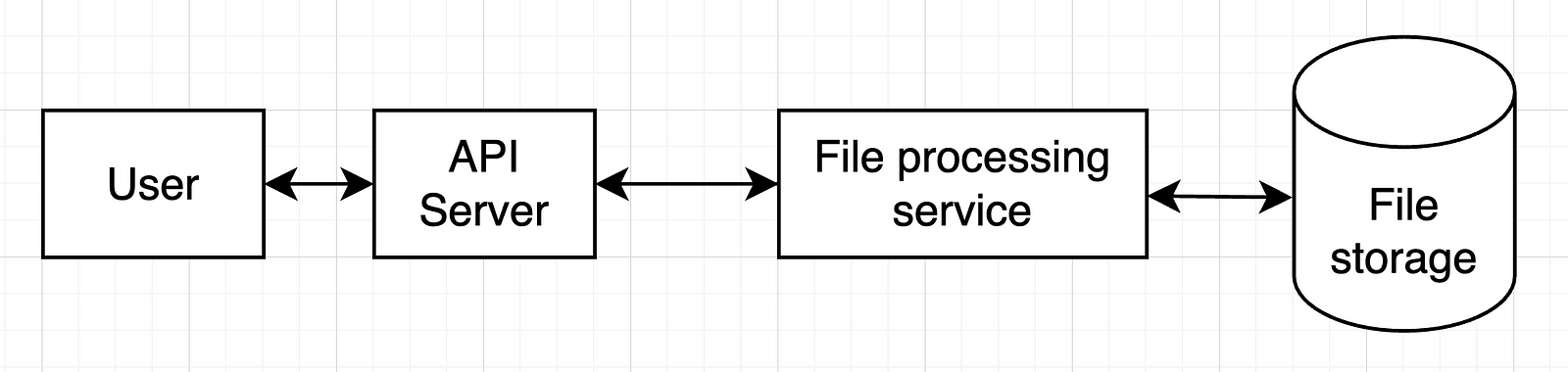

v0: prove it works

The early version was rough, but functional.

The idea was to make it free, so people would actually use it and I’d get some feedback. It had to be friction-free.

I tested it with real CVs and invoices. I posted in indie Discords to get feedback, asking people what they’d actually use it for.

One thing became clear: I didn’t need to support every document type. I needed to be amazing at just a few — like resumes, invoices, and RFPs.

Iterating

v1:

- .zip upload support

- Field templates (e.g., pre-fill “name” and “email” for resumes)

- Date formatting, better validation

v2:

- Usage analytics (without storing docs)

- Email capture → no sign up yet, but I you’d still need to give your e-mail address

- Templates for RFPs and proposals

v3:

- Auth system + Supabase-backed user DB

- Credit management service

- Payment flow & webhook integration

- A cleaner, more secure pipeline

Every iteration made it more robust, less hacky, and closer to a real SaaS.

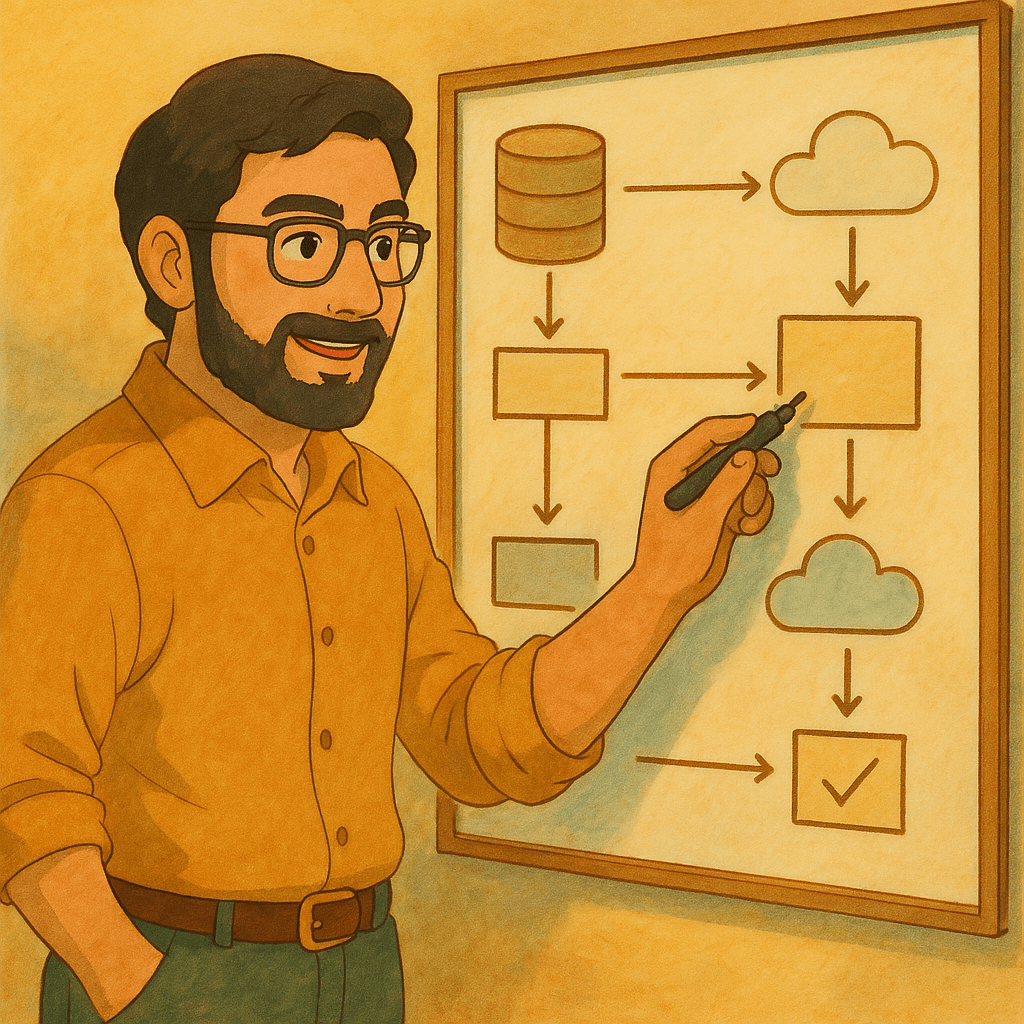

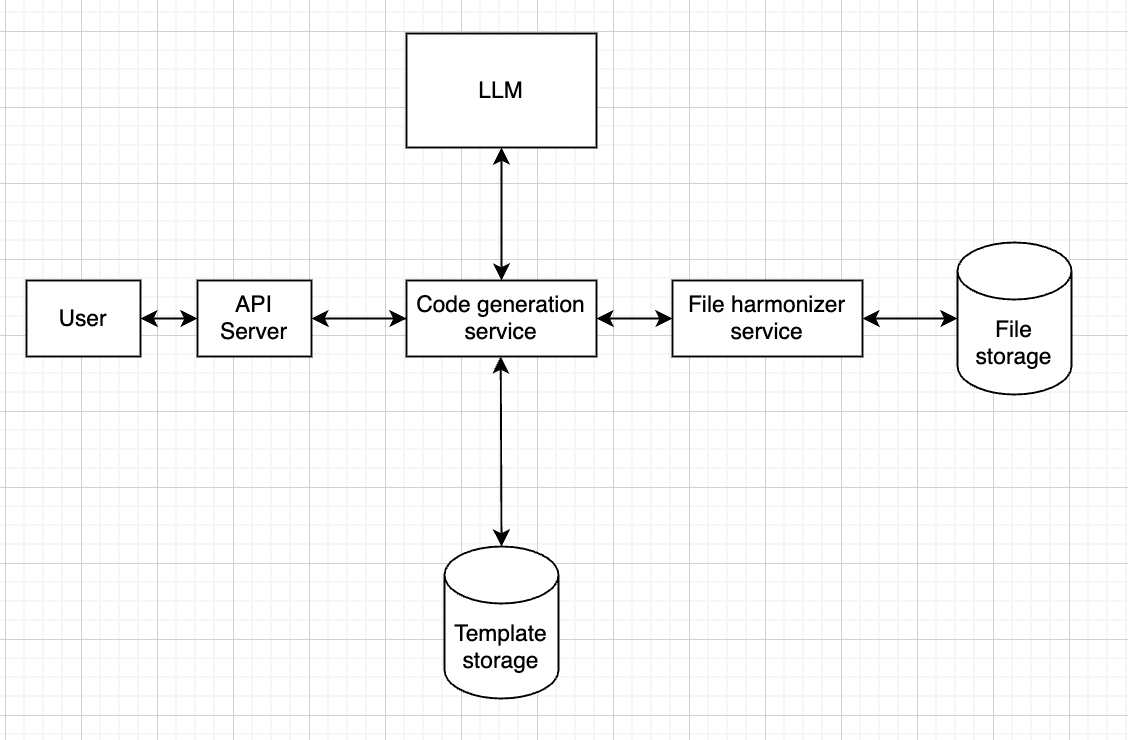

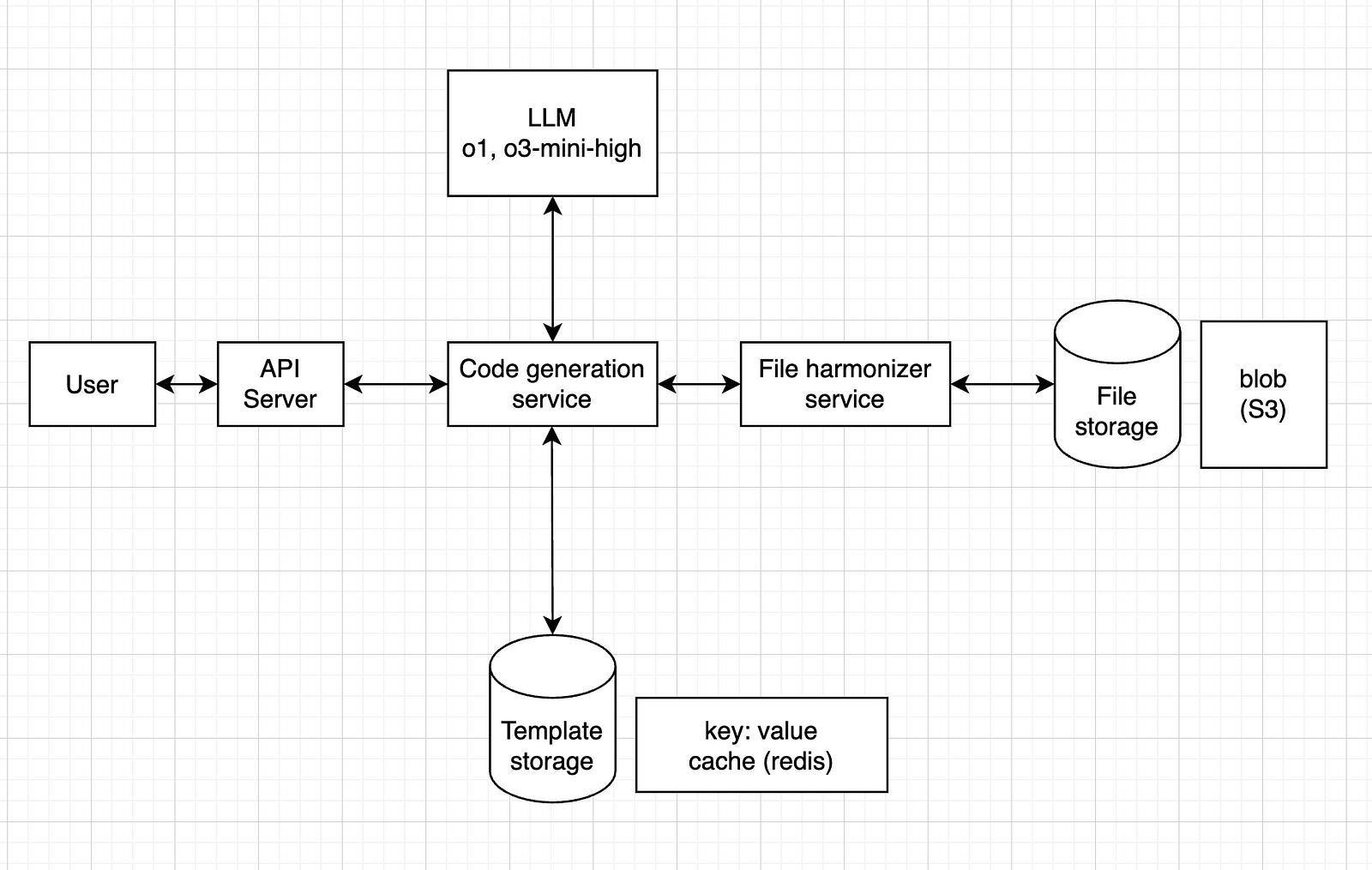

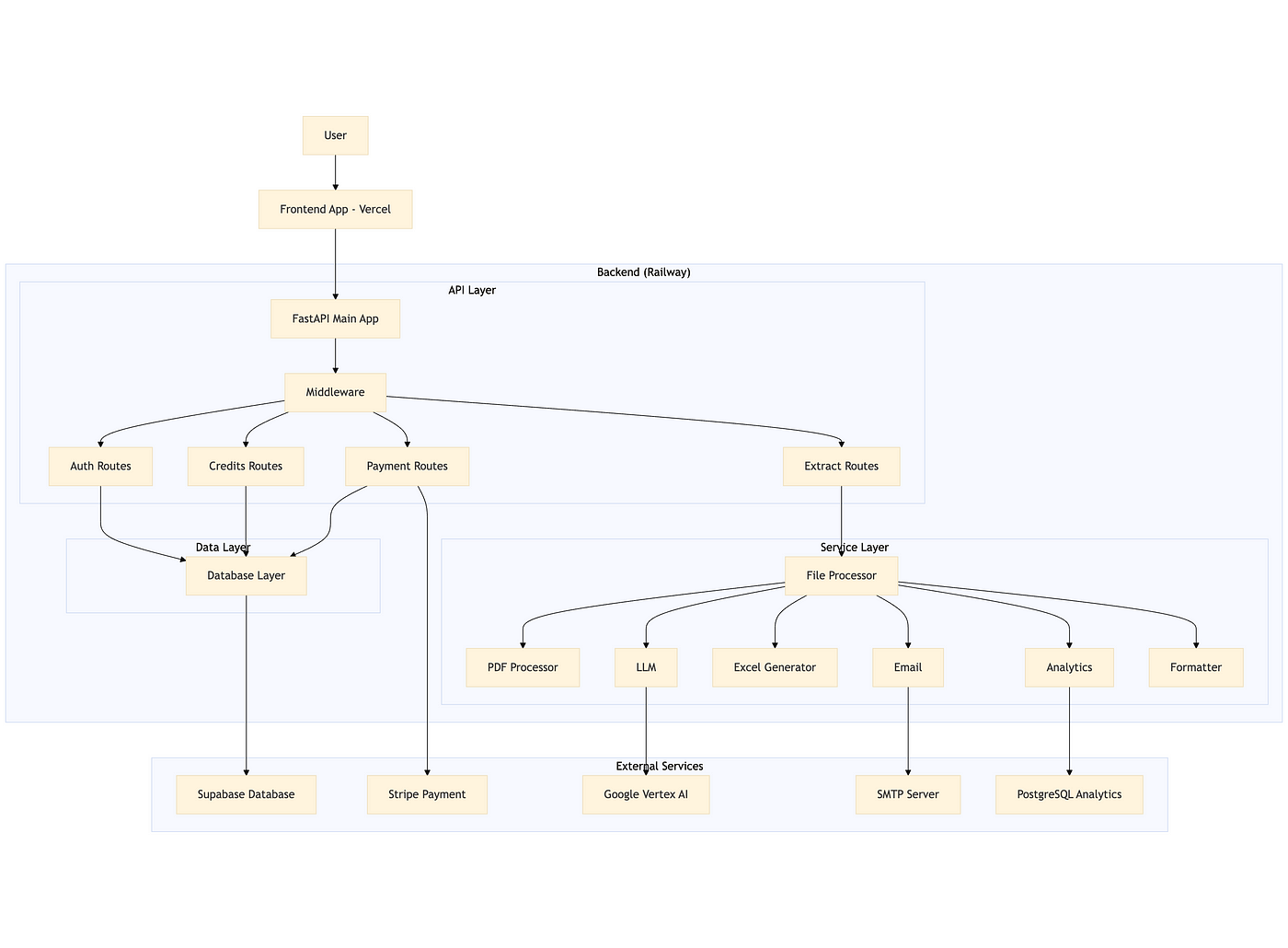

System Architecture (v3 overview)

ZapDoc consists of a Vercel-hosted frontend and a Railway-hosted FastAPI backend.

The core value proposition is simple: upload PDF documents, specify which fields you want to extract, and receive structured data in Excel format via email.

Technical Stack

- Backend: FastAPI (Python) running on Railway

- AI: Google Vertex AI (Gemini)

- Database: Supabase (PostgreSQL)

- Payments: Stripe

- Frontend: React (Vercel)

- Analytics: PostgreSQL

Core Implementation

1. FastAPI app

The backend is modular, with clear separation between API routes, services, and data models.

Middleware enforces CORS and HTTPS, and all routes are grouped by function (auth, extract, credits, payment).

2. Authentication & authorization

Authentication is handled via Supabase JWT tokens. The backend validates tokens on every request using a dependency-injected function, ensuring only authenticated users can access protected endpoints.

3. Document processing pipeline

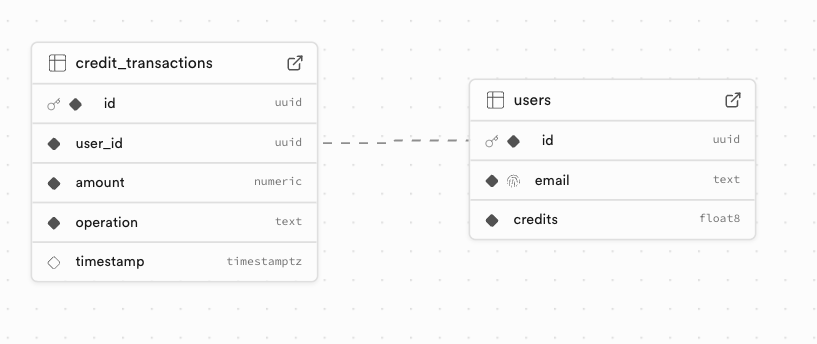

Credit validation

Before processing, the system checks if the user has enough credits (1 credit per page). This is done atomically to prevent race conditions, using asyncio locks and optimistic locking at the database level.

Page counting

The backend counts the total number of pages across all uploaded PDFs and ZIPs (containing PDFs) using PyPDF.

PDF text extraction

Text is extracted from each PDF using PyPDF, with robust error handling for malformed or encrypted files.

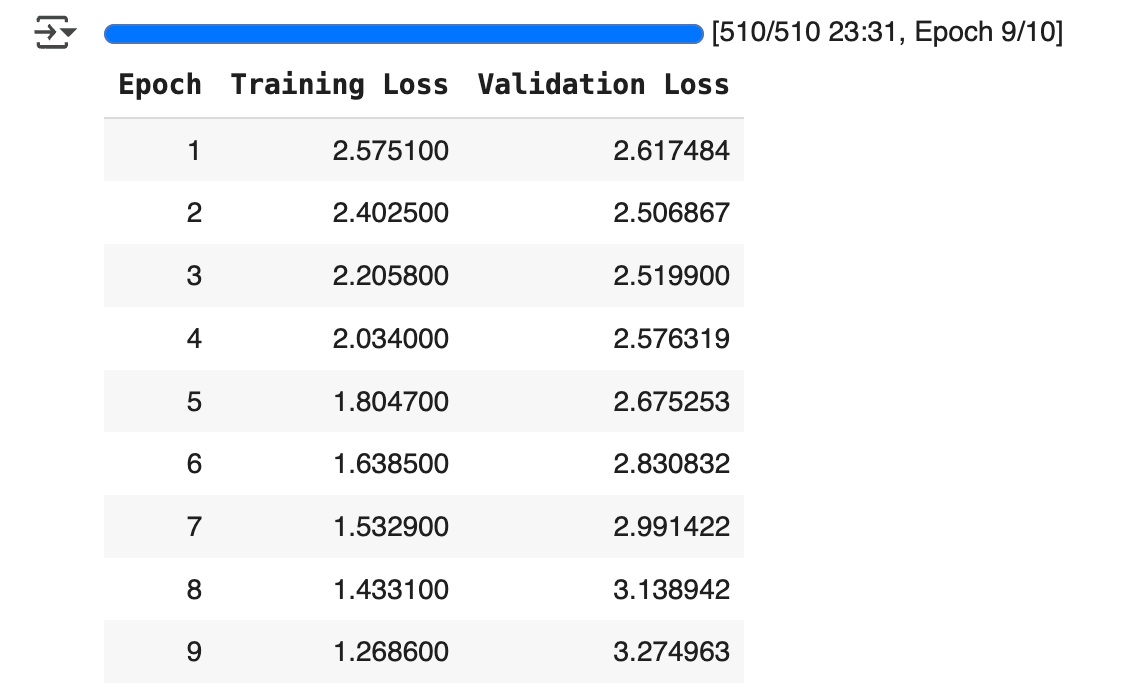

AI-powered field extraction

The extracted text is sent to Google Vertex AI (or OpenAI as fallback) with a prompt to extract only the requested fields. The response is parsed and validated, using the json_repair library to handle malformed JSON.

Document classification

For analytics, the document is also classified (invoice, receipt, contract, etc.) using the same LLM service.

Excel generation

Extracted data is written to an Excel file using OpenPyXL, with the first row as headers and subsequent rows as data.

A header column is included, with the file names.

Email delivery

The resulting Excel file is sent to the user via SMTP, using a styled HTML template and proper attachment handling.

4. Atomic credit operations

All credit operations (add/spend) are atomic. The backend uses asyncio locks and checks the current credit balance before updating, retrying if a concurrent modification is detected.

5. Payment integration

Stripe is used for purchasing credits. The backend creates a checkout session and listens for webhook events to credit the user’s account after successful payment.

6. Analytics

The processed documents themselves are not stored, but the type (resume, etc.) and status (error / success) is logged to a PostgreSQL analytics database for monitoring and future insights.

Key technical challenges & solutions

By far, the most challenging part for me was setting up the whole thing in a way that it wouldn’t have major security flaws.

In short, when I set the credit/payment part, I wanted to make sure that users couldn’t bypass the payment system somehow, nor get other users’ email addresses.

Since this is the part I’m the least comfortable with, I had a lot of help from ChatGPT.

Things like path traversal protection, user isolation, CORS, middleware, etc. are still not 100% clear to me, but this project helped me get a better understanding of them.

Some other stuff to keep in mind

- Race conditions: Solved with asyncio locks and optimistic DB updates.

- LLM response robustness: Used json_repair and strict field validation.

- PDF extraction reliability: PyPDF with error handling and support for ZIPs.

- Performance: Async I/O, efficient batch processing, and proper resource cleanup.

Database Schema (Supabase)

Branding, naming & launch

I wanted something simple, memorable, and descriptive.

After a few brainstorms, I landed on ZapDoc, because it zaps your documents into structured data.

The name stuck.

I described the project to ChatGPT and asked it to draw a logo.

Its first suggestion wasn’t amazing, but it was good enough, so I kept it:

Then came the social and launch planning: Medium, LinkedIn, X, Bluesky, Discord, Uneed, Product Hunt… I’m still rolling that out now.

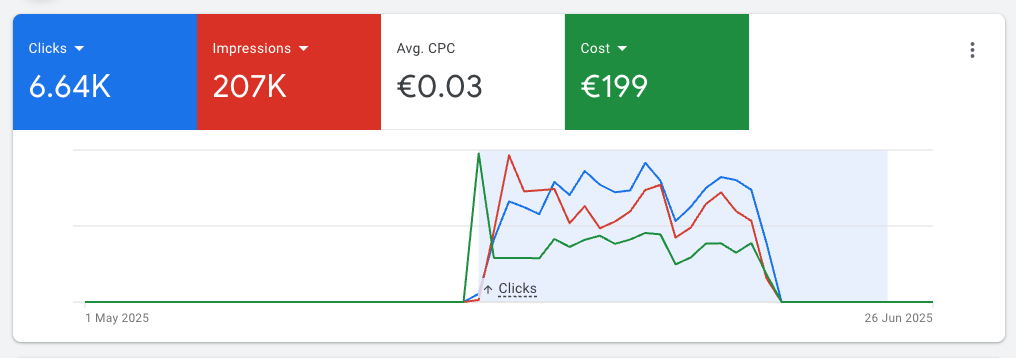

To get some validation for the product, I launched this free version and even ran some Google Ads campaigns for it (~200 euros over 3 weeks)

That brought a lot of people to the tool, but not many users:

Plus, I saw that once the ads stopped, traffic was basically over.

This indicates that people who tried it before didn’t really stick to it.

Either the tool is not useful, or I’m not reaching the right people.

What I learned (so far)

- Start with a niche: you can’t beat GPT-4 at “generic doc parsing”, but you can win at “extract line items from French invoices”.

- Atomicity matters: especially when money is involved.

- AI output isn’t perfect: you need robust validation & formatting layers.

- Building is much easier than selling: it became much easier to build powerfull tools with the help of AI. Making people pay for them is much harder than I expected.

To be honest, I’m still struggling with the niche part: from the usage stats, it seems that most people use it to parse CVs (I thought it would be contracts). But that’s still too generic, so I’ll try to narrow it down once I get more usage data.

What’s next

For v4 and beyond, I’ll try to run ads again (but put less money this time), to see if now people are willing to actually sign up and pay.

If that happens, then I’ll work on some more technical improvements. Some ideas I have in mind for this:

- Move logs from Railway to Supabase for better observability

- Expose an API, so people can integrate it into their own tools

- Add more document types (contracts, tenders)

- Allow users to store custom lists of fields

Final thoughts

ZapDoc is still small.

But it works, and it helped me learn a lot of useful stuff.

Now, I want to crack the sales part, so I can help real users automate real work.

If you’re building with LLMs, don’t chase the hype. Solve a boring problem really well.

Make it work, then make it pretty.

That’s what I’m trying to do.

You can test it here: https://zap-doc.vercel.app/

Let me know what you think. Always happy to chat.

Feel free to reach out to me if you would like to discuss further, it would be a pleasure (honestly):