My top 10 book picks from 2024, to help you build your 2025 reading list

This year, for some reason, I found myself reading a lot more than usual — 52 books in total — without even pushing myself.

I think it happened naturally because I bought many books that genuinely interested me (I also tackled some really short ones, to be fair).

Here are some of the best books I read this year to help you build your reading list for 2025.

But before we dive in, you might be wondering why bother with this. Why create a reading list or read books at all? Well, reading is one of the best things you can do for yourself. There’s so much knowledge out there from experts in various fields — Nobel laureates, Harvard PhDs, and more. Books are affordable, and most of them are really enjoyable to read.

And why books? Why not just read blog posts?

A good book is like a painting: the author invests a lot of time, does extensive research, and works tirelessly to distill their ideas into the pages. That effort really shows.

Good books have layers and depth. Re-reading them reveals new insights each time.

This applies to both fiction and non-fiction. These days, self-development books are selling really well, partly because their titles are so straightforward: “How to Win Friends and Influence People,” “How to Talk to Anyone,” “Think and Grow Rich”.

There’s nothing wrong with that, but remember that many of those lessons can also be found in fiction, presented in a more friendly and subtle way.

Plus, reading doesn’t have to be just for learning — it can also be purely for fun!

Personally, I like to mix things up. This year, I read a lot of fiction, economics, and data science books.

Now, onto the list.

Less Technical Stuff

Build

Tony Fadell’s memoir and practical guide for entrepreneurs offers insights from his experiences designing iconic products like the iPod and Nest.

It’s a rare book written by someone who has actually built things. It covers everything from HR to marketing to legal issues and walks you through the different stages of building a business — from working on a product with a small team to managing an organization of over 400 people.

The Capitalist Manifesto

This book argues in favor of capitalism as the ultimate system for freedom, innovation, and wealth creation.

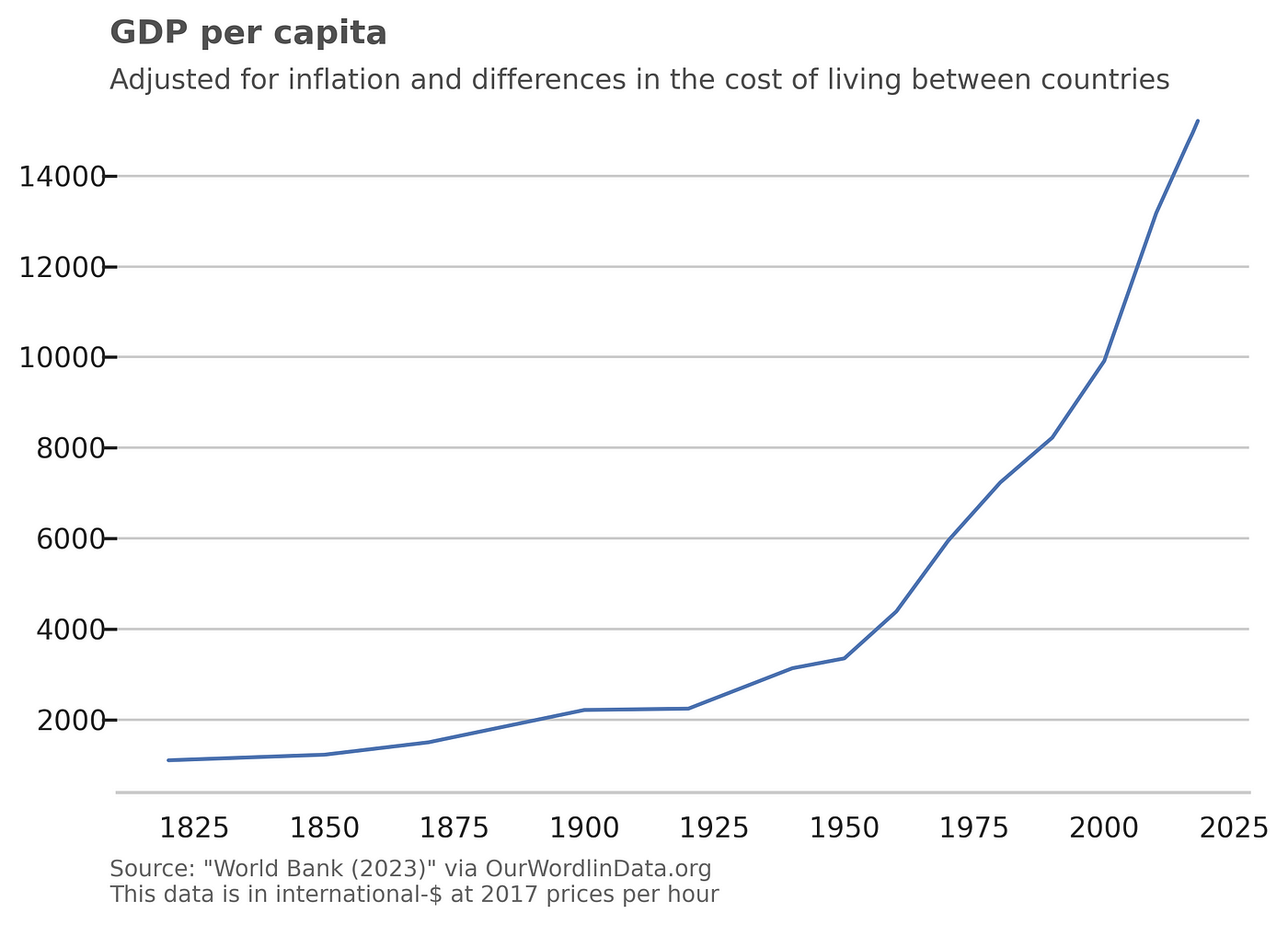

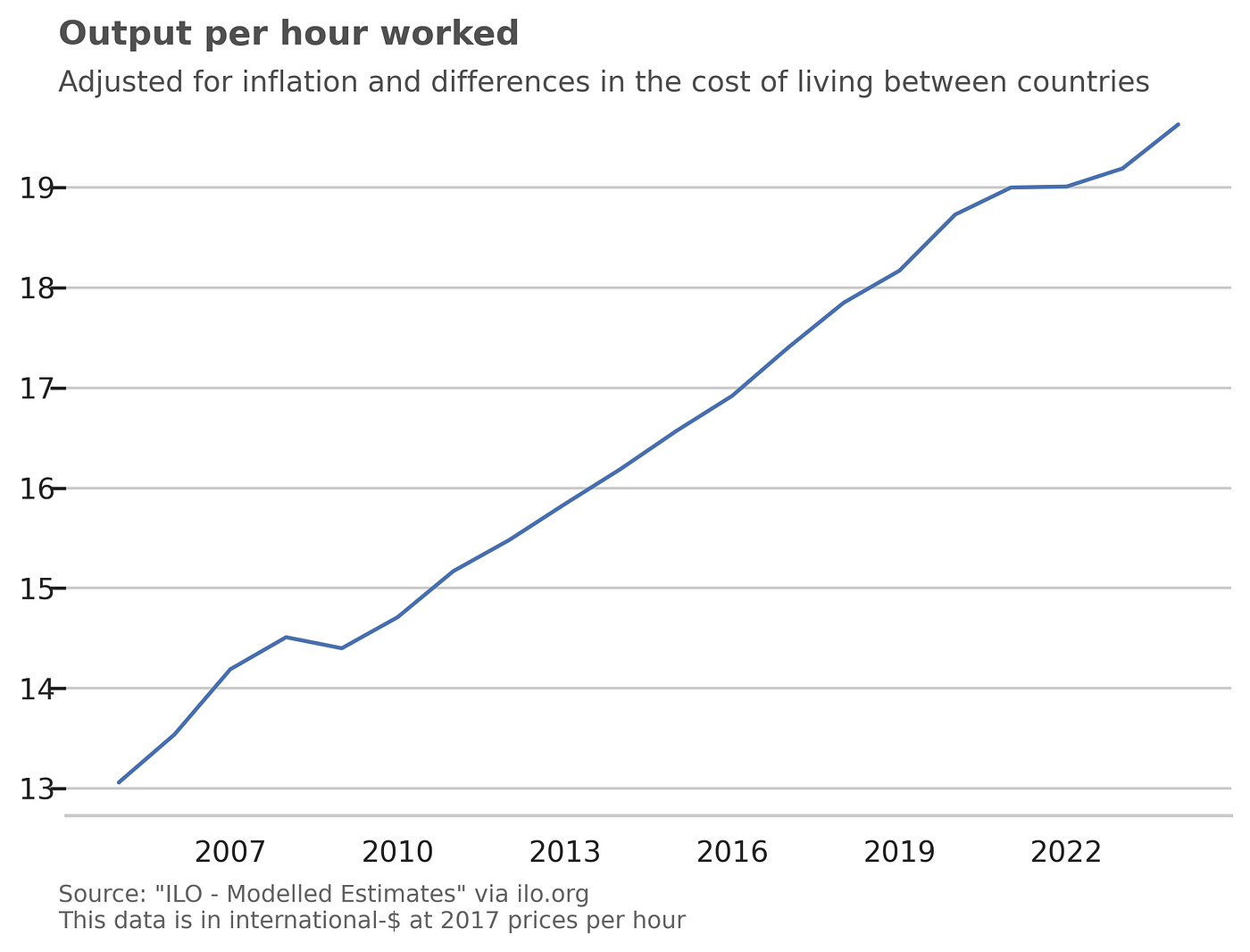

Contrary to popular belief, global free-market capitalism has been the main driver of prosperity, reduced inequality, and fostered innovation over the past few centuries.

While some of the author’s claims come across as naive and heavily biased toward capitalism (for example, suggesting capitalism has a net positive impact on the environment), most arguments are solid and backed by strong data. Absolutely worth reading.

The Chronicles of Narnia

A classic fantasy series by C.S. Lewis about children discovering a magical world full of adventure, talking animals, and profound moral lessons.

The seven books are an allegory of biblical stories, spanning from the creation of Narnia to its end. Remember Aslan, the talking lion from the movies? He symbolizes God, which is made very clear in the books, as he serves as a benevolent and just king/father figure.

Though I’m not religious, I found it fascinating to see the lessons built into the narrative. Regardless of your beliefs, many of these lessons are universal, and reading these books with your children can be a great way to pass those values on.

Educated

Tara Westover’s memoir chronicles her journey from an isolated, fundamentalist upbringing to pursuing education and self-discovery. I couldn’t put it down.

Tara’s parents were extreme conspiracy theorists who refused to send their kids to school or take them to the hospital, believing these institutions were part of a larger scheme to control people. While their worldview might seem absurd at first, it’s heartbreaking to see its impact on their children.

Despite this, Tara managed to escape that environment and eventually earned a doctorate from the University of Cambridge. Safe to say, she turned out okay.

The Power of Creative Destruction

This book explores how innovation drives economic growth and progress by disrupting and replacing outdated systems.

For me, the main takeaway is that demonizing either free-market competition or state intervention doesn’t make sense. Both are necessary, and the book does a great job explaining when government intervention is helpful and when it can cause more harm than good.

Factfulness

This book illustrates global progress by plotting GDP per capita against life expectancy and categorizing countries into four development levels along this axis.

Interestingly, most countries fall in the middle, with only a few being extremely poor or very rich. Almost all countries, however, are moving in the right direction.

It’s remarkable how life has improved globally over the past 100 years. What’s even more surprising is how wrong people often are about the current state of the world. The author surveyed people worldwide, asking specific questions about statistics like vaccination rates, and the results showed widespread pessimism.

This negativity is partly due to the media’s tendency to focus on bad news. While the world isn’t perfect, things are steadily improving, and this book is a great reminder of that.

More Technical Stuff

Fundamentals of Software Architecture

Especially with the rise of generative AI, we’re often asked to build tools that don’t require much data science — just smartly calling APIs and wrapping them in a Streamlit interface.

This calls for a better understanding of software architecture.

All data scientists can benefit from learning software architecture principles. We tend to focus heavily on coding without understanding how our work fits into larger systems. This book offers a comprehensive guide to designing better systems.

Clean Code

A practical guide to writing clean, maintainable, and efficient code, this is a classic in the field.

It’s particularly useful for data scientists like me, who learned coding through Jupyter notebooks and picked up some bad habits along the way. Trust me, clean code matters — it improves readability and reduces bugs.

While it’s a great book, much of it could be distilled into a list of dos and don’ts (which I might create in a future story). However, keep in mind it’s very Java-specific.

System Design Interview

This preparation guide for system design interviews explains frameworks and best practices in a clear, concise way, making it easy to understand.

It’s a great starting point for learning system design concepts, regardless of whether you actually have an interview coming or not.

Causal Inference in Python

This hands-on guide shows how to apply causal inference methods using Python for real-world data science problems.

It borrows heavily from econometrics, so it’s an excellent resource if you come from that background. If your prior exposure to causality has been through machine-learning-focused sources, this book provides a refreshing new perspective.