A pragmatic approach for interviews

I’ve been studying system design on my own and I feel that, as data scientists and AI engineers, we don’t see it enough.

At the beginning I was a bit lost, didn’t know many of the terms used in the domain.

I watched many Youtube tutorials, and most of them go into a level of detail that can be overwhelming if you’re not a software engineer.

Yet, many AI engineering jobs these days have a system design step in the recruiting process.

So, I thought it’d be a good idea to give an overview of what I’ve learned so far, focused on AI engineering.

This tutorial will be focused on system design interviews, but of course it can also help you learn system design in general, for your job.

I’ll be using a framework from the book “System Design Interview”, which suggests the following script for the interview:

- Clarifying questions

- Propose high level design and get buy-in

- Deep dive

- Wrap-up: refine the design

I’ve adapted this framework to make it more linked to AI Engineering, as well as more pragmatic, by outlining what I consider to be the minimum output required in each step.

And, for this tutorial, I took a question that I’ve seen in interviews for an AI Engineer position:

“Build a system that takes uploaded .csv files with different schemas and harmonizes them.”

So, let’s design!

Clarifying questions

In this first step, you should ask some general questions, to have a better view of the context of the problem, and some more specific ones, to define the precise perimeter you’re working on.

More specifically, you should end this step with at least this info:

- context

- functional features

- non-functional features

- key numbers

Context

Ask things like:

- who will be using this?

- how will they be using it?

- where they will be using it (ex.: is it just one country, or worldwide)?

In our case, the system will be used in-company, to format multiple .csv files that come from different sources.

Their format and schema can always be different, so we need a robust and flexible solution that handles well this variability.

Those files will be uploaded by users, that don’t need the file right away: they just need it to be stored somewhere for later use by other systems.

It’s a small company, and they are all more or less in the same place.

Functional features

These are the things the product/service should be able to do.

In our example, there’s only one main functional feature: convert file.

But, we can also split that into 3 steps, which will help ups design our system later:

- upload file

- process file

- store file

In a more complex app, like YouTube, functional features could be:

- upload video

- view video

- search video

- etc.

Make sure the interviewer is onboard with these. In a real-life situation, you’d have things like authentification, account creation, etc.

Non-functional features

These are things that your system should consider, like: scalability, availability, latency, etc.

In practice, there’s a few ones that you should almost always consider:

- latency

- availability vs. consistency

Latency means: what’s an acceptable time for the user to get a response?

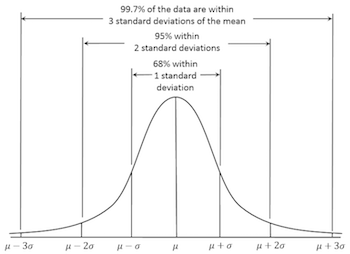

The availability vs. consistency tradeoff refers to the idea that in a distributed system, you can’t always guarantee both that data is immediately consistent across all nodes and that it’s always available when requested — especially during network failures.

Example: Imagine a banking app where a user transfers money from their savings to their checking account. If the system prioritizes consistency, it might temporarily block access while syncing all servers to ensure the balance is accurate everywhere. If it prioritizes availability, it might show the new balance immediately — even if some servers haven’t updated yet — risking temporary inconsistencies.

In some services, availability is more important. In others, consistency is more important.

Don’t look at this at the system level, but at the level of each functional feature.

Our use case is very simple, with only one functional feature, and the choice between consistency and availability will depend on the type of data and how it’s used, so check with the interviewer.

For the latency, let’s assume anything under 1 minute is acceptable.

Key numbers

This will help you calculate the amount of data that goes through your system, as well as the storage needs.

In our use case, some important figures could be:

- daily active users (ex.: 100)

- files per user (ex.: 1)

- average file size (ex.: 1 MB)

With these 3 numbers, you can already estimate the data volume:

- daily: 100 x 1 x 1 MB = 0.1 GB

- yearly: 0.1 GB x 365 = 36.5 GB

Those numbers will help us choose the best solutions for processing and storage.

For this example, let’s also assume there isn’t huge variance in the file size (there won’t be files over 10 MB).

Propose high-level design and get buy-in

With all this in hands, it’s time to start designing.

The minimal output here would be:

- core entities

- overall system design

- address functional requirements

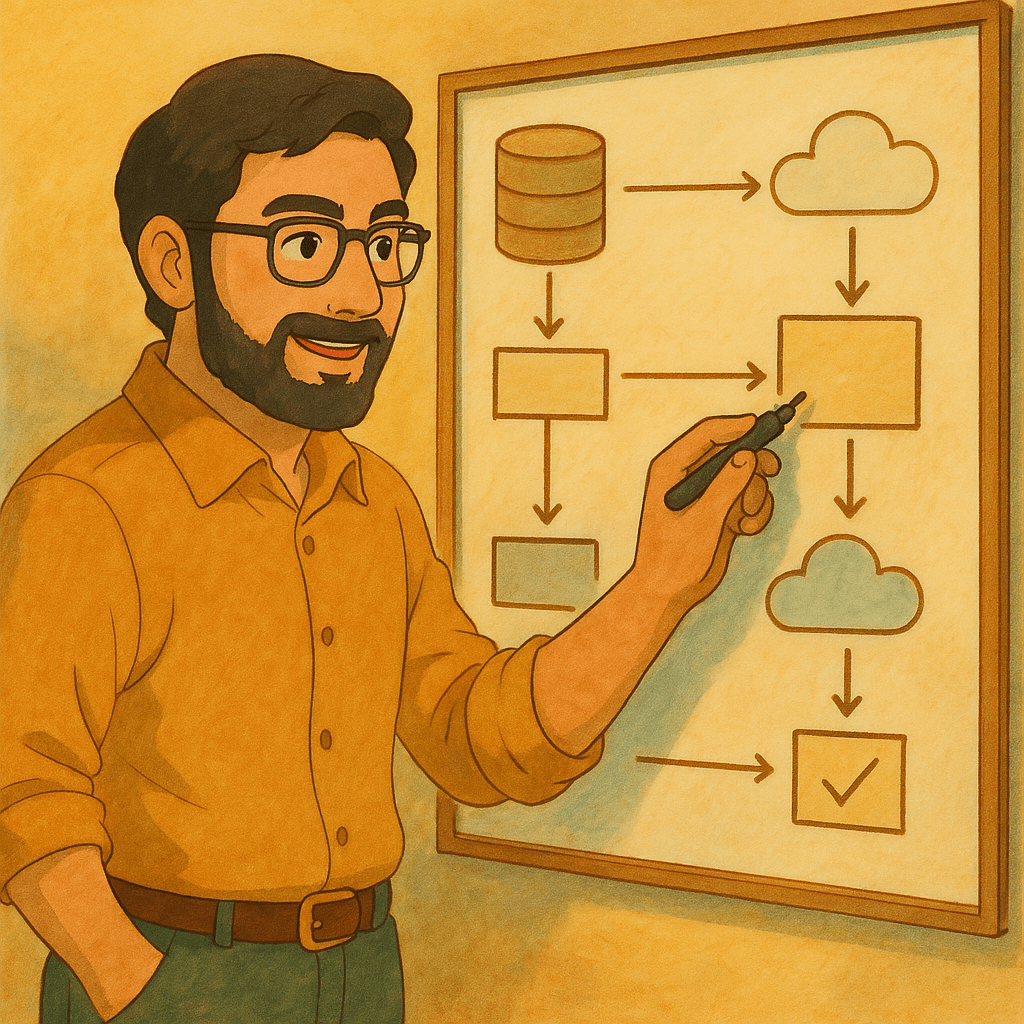

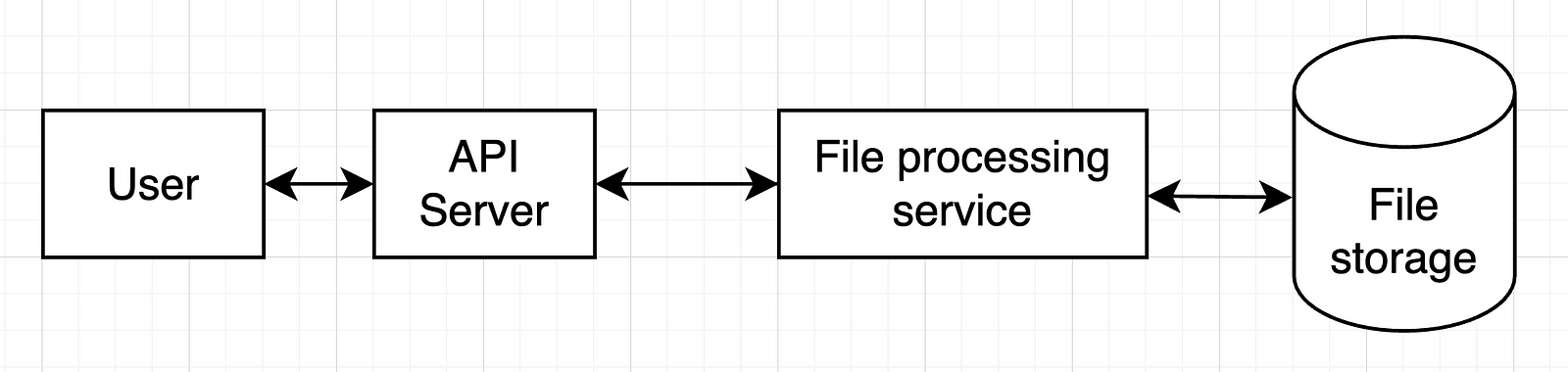

A single server design is a reasonable starting point for most use cases.

So, start with a user, a server, services and databases.

In our example, we can start with only one service, so the whole setup would look like this:

In a more complex system, we’d have more services and more databases.

Check with your interviewer if they’re OK with this and move on.

Deep dive

Now it’s time to detail the most important components of our previous design. That’s obviously the file processing service.

The minimal output:

- address non-functional requirements

But it’s also good to have these (check with the interviewer what they are expecting):

- API detail

- data schema detail

- tool choices

In our case, we should think in more detail on how those files would be processed.

My approach here (since we’re focused on AI solutions) is to use an LLM for this:

- Give the LLM a “gold standard” format for our .csv files (column names and formats)

- Give it a sample of the file to transform too (column names and formats)

- Ask it for code that converts the file into the desired format

- Run that code on the uploaded file

- Store the resulting file

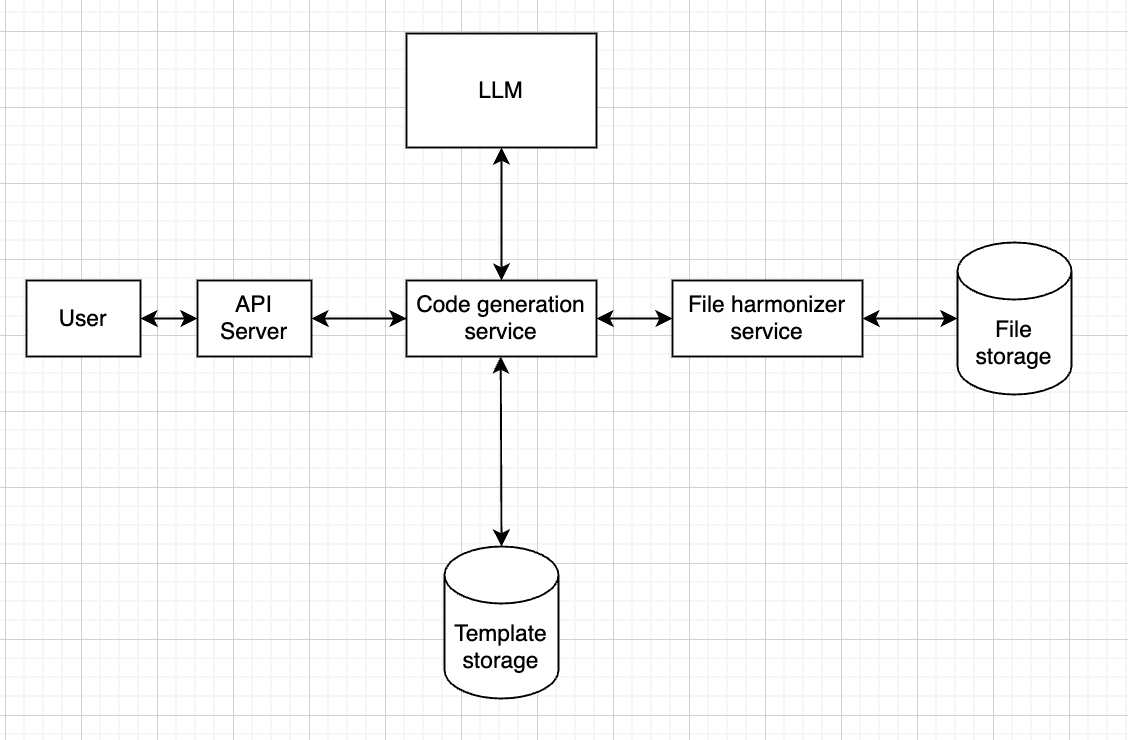

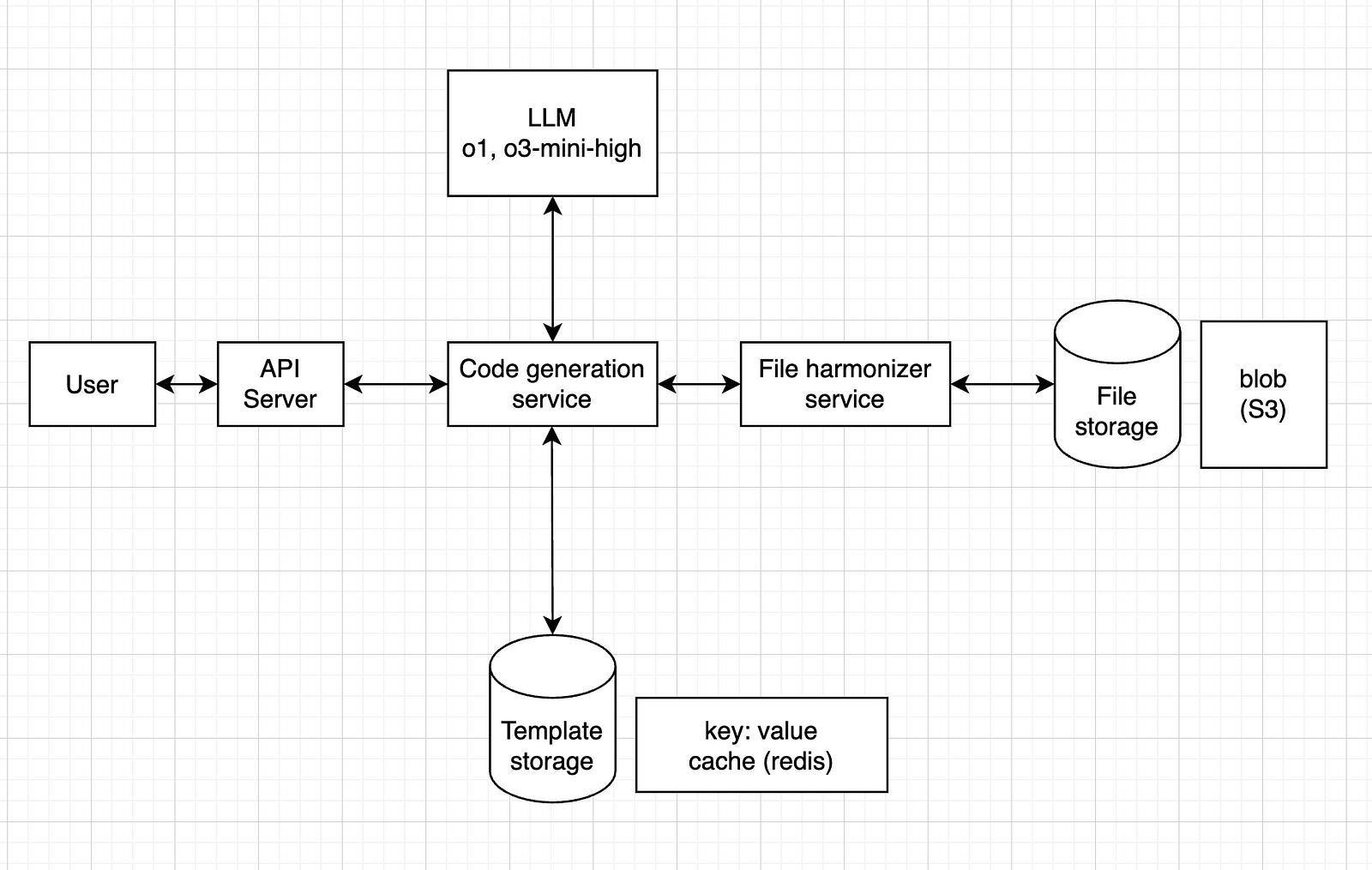

With this approach in mind, we can then look back into our design and what changes we should make to it:

- We should probably separate code generation from code running, since these serve completely different purposes

- There might be times when we get a file schema that we’ve seen already. In that case, we can have some sort of storage that allows us to cache code used before.

This would result in something like this:

Meaning that the code generation service will first check in “template storage” if we have seen this format before.

If so, it will fetch the code from that storage and send it to the file harmonizer service.

If not, then it will call the LLM.

Now, one of the non-functional requirements was a latency under 1 minute.

Given the average file sizes, it’s reasonable to assume the whole thing will take less than 1 minute to run.

In terms of technical choices, a few things are relevant here:

- the type of model

- the type of storage

For the model, any model should do it, but I think it’s safer to go for a reasoning model, such as o1 or o3-mini-high.

For the file storage, since it’s just .csv files, a blob storage service like Amazon S3 should work.

For the template storage, we could have a key: value system, where the key is the schema (or a hash version of it) and the value is the corresponding code (or maybe a path to a blob storage with the .py file). One tool that can do this is Redis.

So, our final design would look like this:

Wrap up

In this step, we can refine our design, or at least find improvement opportunities.

Essentially, show what could be improved if you had more time.

In our case, here are some examples:

- a first iteration loop: what happens if the code fails to run? How do we call the LLM again, with the error message, to ask for new code?

- a fallback system: if the code fails n times in a row, how can we make sure it stops trying, and gives some error message to the user, instead of running an infinite loop?

- backup: how can we make sure our file storage has some sort of backup?

- simultaneous requests: how can we handle cases where multiple users upload at the same time? Should we use a message queue system?

The idea is to find bottlenecks, single points of failure and things like that, to improve on.

Conclusion and additional resources

I’ve seen many resources on system design interviews, and most of them are focused on software engineers, with very complex systems, addressing things that are usually not handled by AI engineers.

Yet, when the interview is for an AI engineer role, the request can often be more like this one: instead of multiple services and use cases, a sort of linear processing system, focused on LLMs, etc.

I’ve read two books on the topic:

“System Design Interview” is more generic, and I found it more useful, giving an overview of how to approach these interviews.

“Generative AI System Design Interview” is more focused on building things from scratch (LLMs, image generation models, etc.), which is not as common as using external APIs.

If you’re more into courses, I can recommend these two:

If you want a more detailed post on the topic, I found this one really useful:

It goes straight to the point, with very practical advice.

And, if you prefer video format, I did one for this tutorial as well:

That’s it, I hope this was useful for you.

I’m not an expert in system design, and I’m aware that the design I propose above can be improved in many ways.

I just wanted to share what I’ve learned so far, focusing more on AI.

Let me know in the comments if you’d do anything different, or if you see any major flaws in that design.

Feel free to reach out to me if you would like to discuss further, it would be a pleasure (honestly):