Use Hugging Face’s smolagents framework to automate customer support for a fashion store

Introduction

Fashion retailers receive hundreds of customer emails every day.

Some asking about products, others trying to place orders. Manually handling these messages is time-consuming, error-prone, and doesn’t scale.

In this project, we tackle this problem by building an AI system that reads emails, classifies their intent, and automatically generates appropriate responses.

Our input consists of two datasets:

- product catalog (including product IDs, names, categories, descriptions, stock levels, and seasonality)

- customer emails (including subject and body text)

Using these datasets, we’ll build a complete pipeline that handles both order requests and product inquiries efficiently.

Our pipeline should process the emails, classifying them as either product inquiries or order requests, and responding accordingly:

- if it’s an order request, it should check if the product is in stock and, if so, update the stock to deduce the requested amount

- if it’s a product inquiry, it should fetch the information about the product

In both cases, the agent should be able to find the right product and write an appropriate answer.

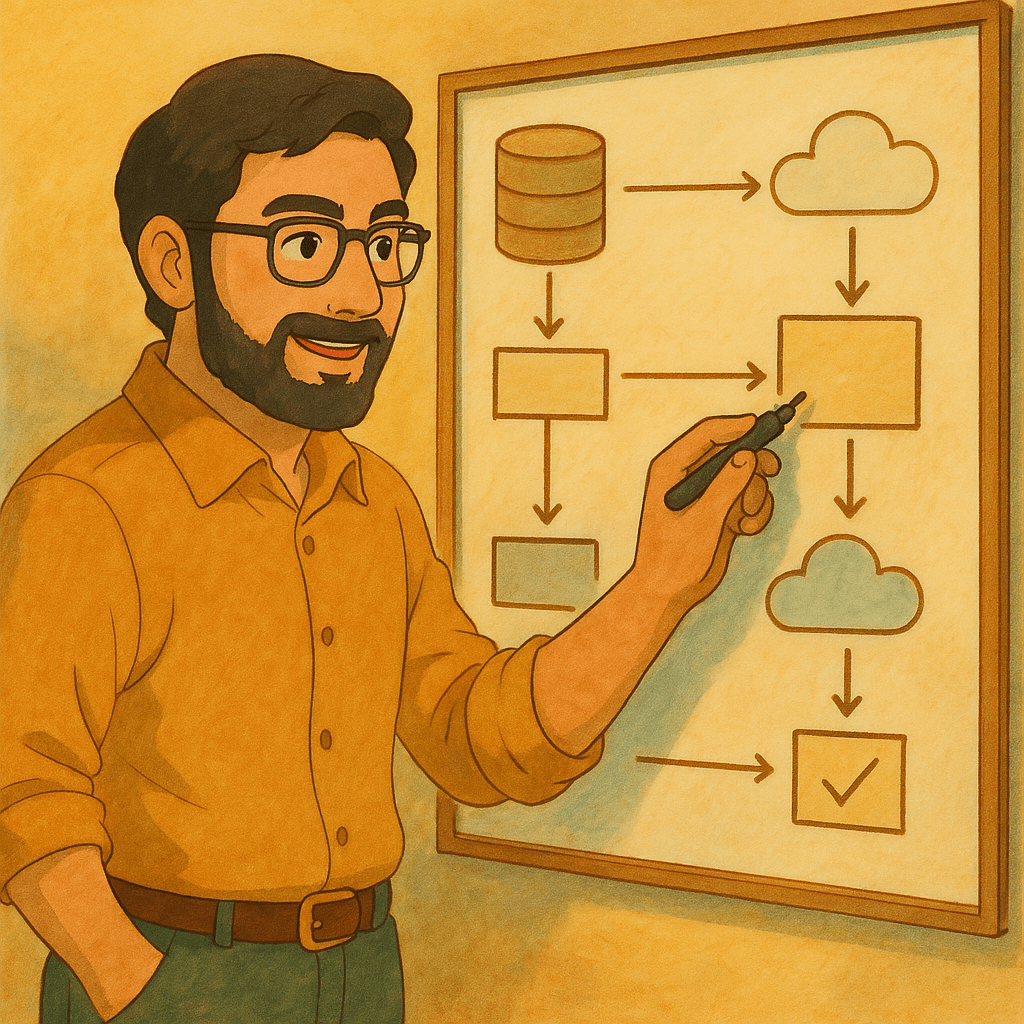

This task combines several modern AI techniques:

- LLM prompting for understanding and generating text

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) for answering queries over large product catalogs

- Vector search (via ChromaDB) to scale efficiently

- Agentic approach and robust workflows with smolagents

The goal is to automate the handling of emails in a way that’s smart, production-aware, and scalable.

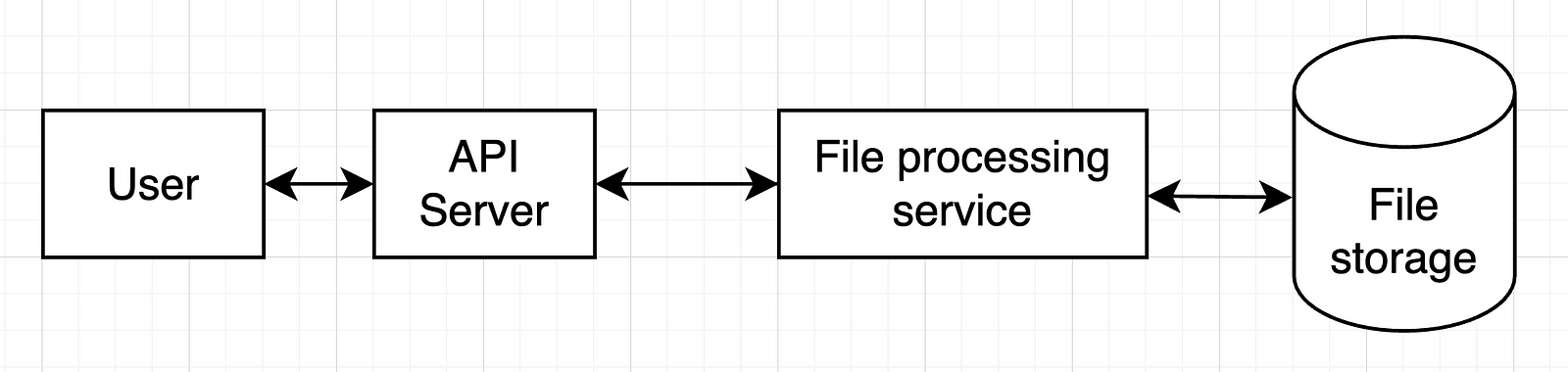

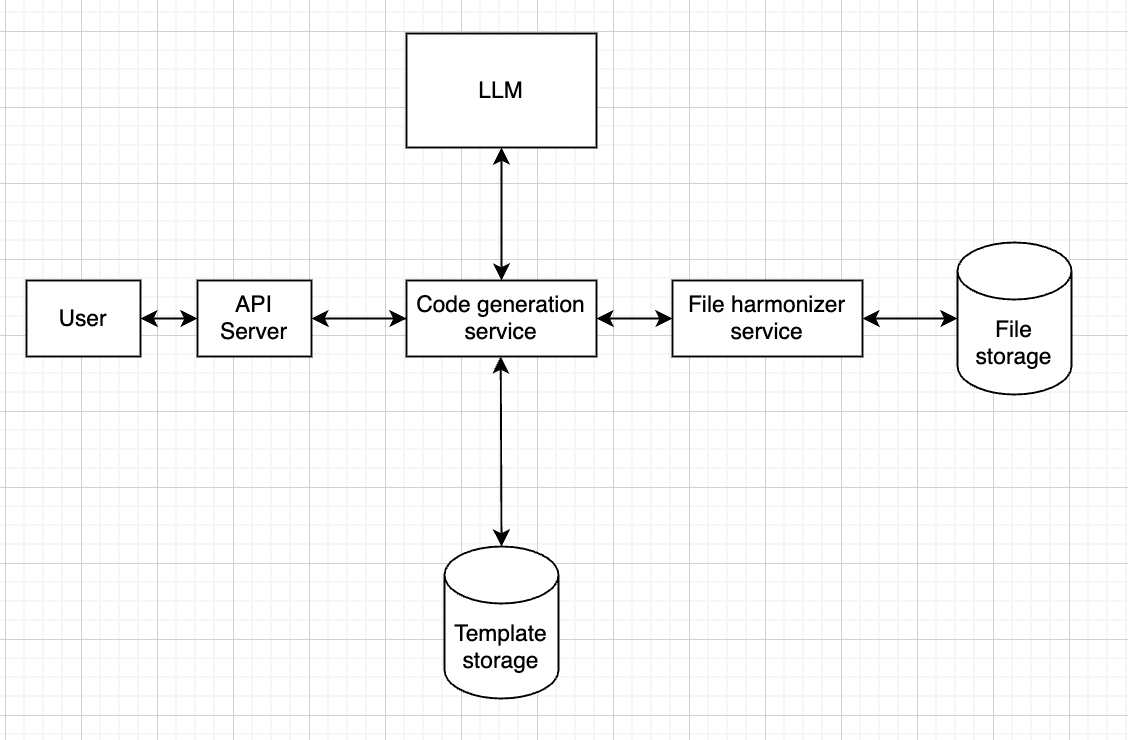

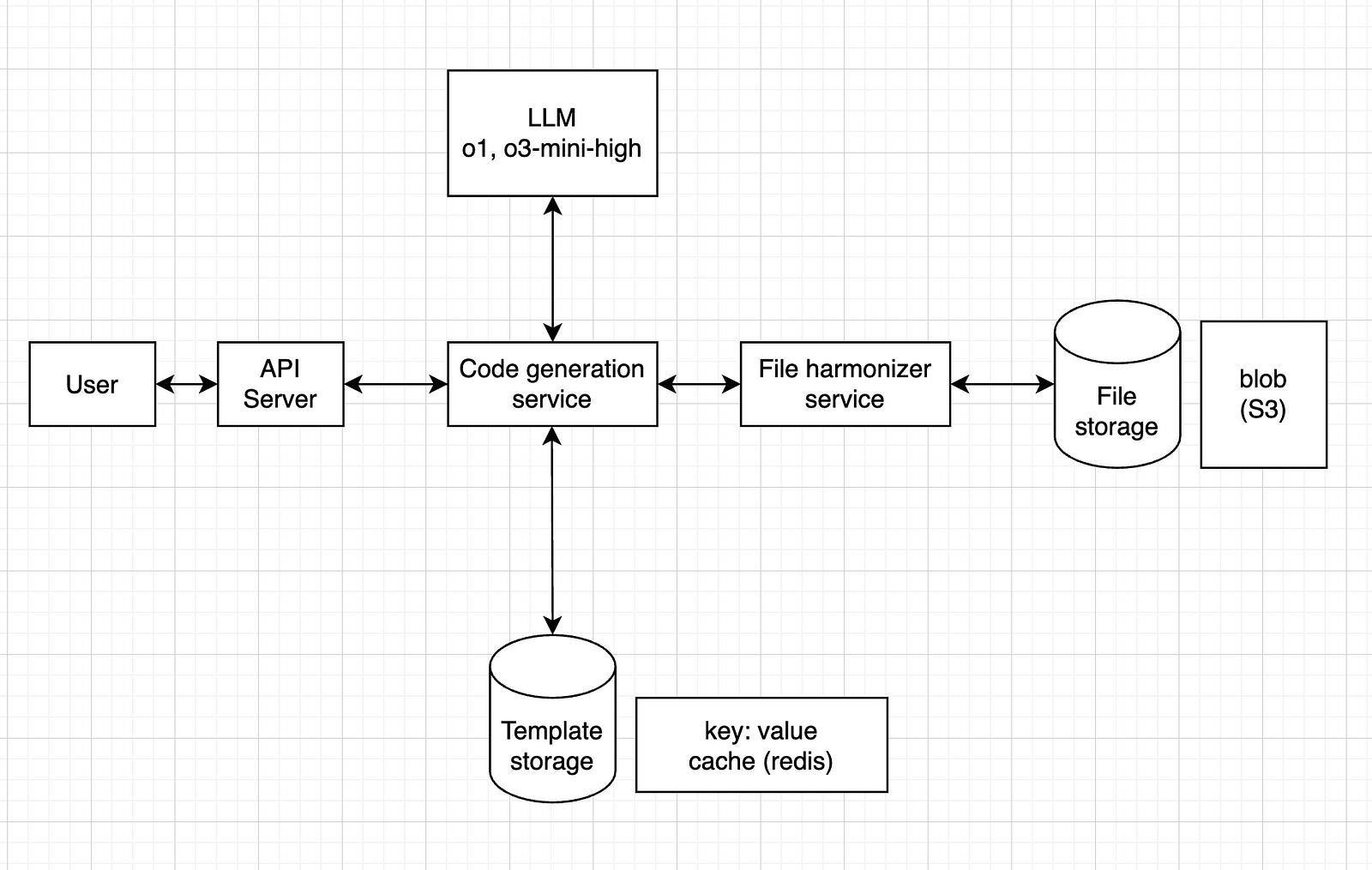

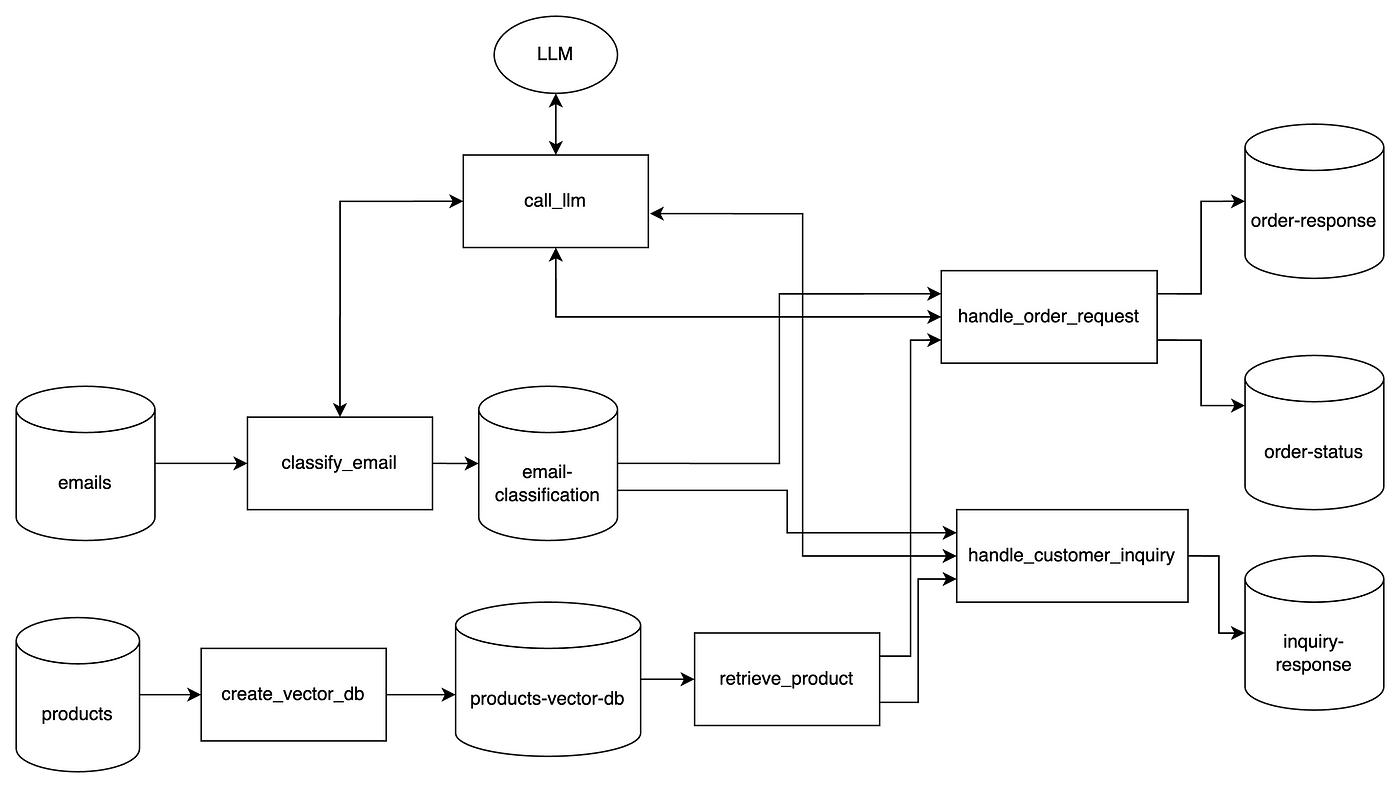

Here’s the overall system architecture:

Now, let’s start building!

1. Setup

In our setup, we just want to install dependencies and prepare some functions that will make our job easier later.

Import required libraries:

%pip install openai httpx==0.27.2 chromadb smolagents json-repairPrepare a call_llm function:

from openai import OpenAI

from google.colab import userdata

import os

os.environ["OPENAI_API_KEY"] = userdata.get('OPENAI_API_KEY')

client = OpenAI()

from pydantic import BaseModel, Field

from typing import Dict, Optional

import ast

class ResponseSchema(BaseModel):

ai_response: str = Field(..., description="AI response")

def call_llm(

system_prompt, user_prompt, model="gpt-4o",

text_format=ResponseSchema):

response = client.responses.parse(

model="gpt-4o",

input=[

{"role": "system", "content": system_prompt},

{"role": "user", "content": user_prompt}

],

text_format = text_format,

temperature=0,

)

return ast.literal_eval(response.output[0].content[0].text)Notice how we set a structured response output. This makes our function more flexible, to handle any type of request.

Read input data:

import pandas as pd

products_df = pd.read_csv('products.csv')

emails_df = pd.read_csv('emails.csv')2. Build the Product Vector Store

We will embed product data using OpenAI, and store the vectors in ChromaDB. It’s a good choice for fast retrieval and setup, keeping things local.

One very important feature here is metadata: we need to make sure this is properly set for enhanced search. For instance, ChromaDB doesn’t handle well filters on array fields, so we turn the “seasons” field into a set of boolean columns.

import chromadb

from chromadb.config import Settings

from chromadb.errors import NotFoundError

products_df["text"] = products_df[["name", "category", "description", "seasons"]].agg(" ".join, axis=1)

def get_embedding(text):

response = client.embeddings.create(

input=text,

model="text-embedding-3-small"

)

return response.data[0].embedding

products_df["embedding"] = products_df["text"].apply(get_embedding)

all_seasons = ["spring", "summer", "fall", "winter"]

for season in all_seasons:

products_df[season] = products_df["seasons"].apply(

lambda x: 1 if "All seasons" in x or season in x.lower() else 0

)

chroma_client = chromadb.Client(Settings())

try:

chroma_client.delete_collection("products_openai")

except NotFoundError:

pass

collection = chroma_client.create_collection("products_openai")

metadata_cols = ["product_id", "stock", "category", "price", "winter","summer","fall","spring"]

for i, row in products_df.iterrows():

metadata = {

col: row[col] for col in metadata_cols

}

collection.add(

documents=[row["text"]],

embeddings=[row["embedding"]],

ids=[str(i)],

metadatas=[metadata]

)3. Create our agent and its first tool

Now, to the juicy part: setting up our agent and it’s tool.

Since we needs to be able to query our product database, we create a function called query_product_db, which takes as input a query and filters.

For it to be a proper tool, our function needs the @tool decorator, a proper docstring, and type hints. This is what allows our agent to know exactly how to use.

In our case, we need our agent to know exactly how to use the metadata filters in ChromaDB, so setting up a few examples is a good idea:

from smolagents import OpenAIServerModel, ToolCallingAgent, tool

from typing import List, Optional

@tool

def query_product_db(query: str,

metadata_filter:dict | None=None,

document_filter:dict | None=None) -> dict:

"""Retrieve the three best-matching products from the `products`

Chroma DB vectorstore.

Args:

query : str

Natural-language search term. A dense vector is generated with

``get_embedding`` and used for similarity search.

metadata_filter : dict | None, optional

A Chroma metadata filter expressed with Mongo-style operators

(e.g. ``{"$and": [{"price": {"$lt": 25}}, {"fall": {"$eq": 1}}]}``).

If *None*, no metadata constraints are applied.

document_filter : dict | None, optional

Full-text filter run on each document’s contents

(e.g. ``{"$contains": "scarf"}``). If *None*, every document is eligible.

Examples

--------

>>> get_product(

... "a winter accessory under 25 dollars, the id is FZZ1098",

... metadata_filter={

... "$and": [

... {"price": {"$lt": 25}},

... {"category": {"$in": ["Accessories"]}},

... {"winter": {"$eq": 1}},

{"product_id""{"$eq": "FZZ1098"}}

... ]

... },

... document_filter={"$contains": "scarf"}

... )

>>> get_product(

... "something for winter",

... metadata_filter={"winter": {"$eq": 1}}

... )

Here's an overview of the product database metadata:

product_id,name,category,description,stock,spring,summer,fall,winter,price

RSG8901,Retro Sunglasses,Accessories,"Transport yourself back in time with our retro sunglasses. These vintage-inspired shades offer a cool, nostalgic vibe while protecting your eyes from the sun's rays. Perfect for beach days or city strolls.",1,1,1,0,0,26.99

SWL2345,Sleek Wallet,Accessories,"Keep your essentials organized and secure with our sleek wallet. Featuring multiple card slots and a billfold compartment, this stylish wallet is both functional and fashionable. Perfect for everyday carry.",5,1,1,0,0,30

VSC6789,Versatile Scarf,Accessories,"Add a touch of versatility to your wardrobe with our versatile scarf. This lightweight, multi-purpose accessory can be worn as a scarf, shawl, or even a headwrap. Perfect for transitional seasons or travel.",6,1,0,1,0,23

"""

query_embedding = get_embedding(query)

results = collection.query(

query_embeddings=[query_embedding],

n_results=3,

include=["documents", "metadatas","distances"],

where=metadata_filter,

where_document=document_filter

)

return results

product_finder_agent = ToolCallingAgent(

tools=[query_product_db], model=OpenAIServerModel(model_id="gpt-4o")

)Finally, we use ToolCallingAgent, which is suited for our use case.

In some other cases, you might want to use CodeAgent (for example, for writing code, obviously).

4. Email classification with LLM

Next step is to ese GPT to classify each email as either an “order request” or “product inquiry” and store results in an email-classification dataframe.

For this we don’t need the agent: a simple call to an LLM is enough:

from pydantic import BaseModel, Field

from typing import Literal

class EmailClass(BaseModel):

category: Literal["order_request", "customer_inquiry"] = Field(..., description="Email classification")

def classify_email(email):

system_prompt = """You are a smart classifier trained to categorize customer emails based on their content. Each email includes a subject and a message body.

There are two possible categories:

• order_request: The customer is clearly expressing the intent to place an order, make a purchase, or asking to buy something (even if casually or imprecisely).

• customer_inquiry: The customer is asking a question, requesting information, or needs help deciding before buying.

Classify the following emails based on their subject and message. Output only one of the two categories: order_request or customer_inquiry.

Do not add any extra text, just the class.

⸻

Examples:

Email 1

Subject: Leather Wallets

Message: Hi there, I want to order all the remaining LTH0976 Leather Bifold Wallets you have in stock. I’m opening up a small boutique shop and these would be perfect for my inventory. Thank you!

Category: order_request

Email 2

Subject: Need your help

Message: Hello, I need a new bag to carry my laptop and documents for work. My name is David and I’m having a hard time deciding which would be better - the LTH1098 Leather Backpack or the Leather Tote? Does one have more organizational pockets than the other?

Category: customer_inquiry

Email 3

Subject: Purchase Retro Sunglasses

Message: Hello, I would like to order 1 pair of RSG8901 Retro Sunglasses. Thanks!

Category: order_request

Email 4

Subject: Inquiry on Cozy Shawl Details

Message: Good day, For the CSH1098 Cozy Shawl, the description mentions it can be worn as a lightweight blanket. At $22, is the material good enough quality to use as a lap blanket?

Category: customer_inquiry

"""

user_prompt = f"""

Now classify this email:

Subject: {email.subject}

Message: {email.message}

Category:

"""

return call_llm(system_prompt, user_prompt, text_format=EmailClass)

email_classification_df = emails_df.copy().rename(columns={"email_id": "email ID"})

email_classification_df[['category']] = emails_df.apply(classify_email, axis=1).apply(pd.Series)

email_classification_df = email_classification_df[['email ID', 'category']]

set_with_dataframe(email_classification_sheet, email_classification_df)5. Handle order requests

Now that everything is set up, let’s handle our first use case: dealing with order requests.

These emails can be tricky they might mention a certain product by its name, ID, or something else. They might mention the quantity they want to buy, or things like “all you have in stock”.

For ex.:

Subject: Leather Wallets

Message: Hi there, I want to order all the remaining

LTH0976 Leather Bifold Wallets you have in stock.

I'm opening up a small boutique shop and these would be perfect

for my inventory. Thank you! So, before we deal with it, we need to extract product requests from emails using structured LLM prompts. For instance, product id and requested quantity. Since quantity might be “all you have in stock”, our agent needs access to the product database to find that information.

Extract structured information

Let’s start extracting structured information from the email, using our agent:

from json_repair import repair_json

order_requests_df = email_classification_df[email_classification_df["category"]=="order_request"]

order_requests_df = order_requests_df.merge(emails_df, left_on="email ID", right_on="email_id")

def extract_order_request_info(order_request):

prompt = f"""

Given a customer email placing a product order, extract the relevant information from it: product and quantity.

The customer might mention multiple products, but we only need those for which they are explictly

placing an order.

Subject: {order_request["subject"]}

Message: {order_request["message"]}

answer should be in this format:

[{{'product_id': <the product ID, in this format: 'VSC6789'>,'quantity': <an integer>}}]

'quantity' should always be an integer. If needed, check the quantity in stock.

If the mentioned product ID does not follow that format (ex.: it contains spaces, '-', etc.),

clean it to follow that format (3 letters, 4 numbers, no other characters)

Here are 2 examples of the expected output:

Example 1:

[{{'product_id': 'LTH0976', 'quantity': 4}}]

Example 2:

[{{'product_id': 'SFT1098', 'quantity': 3}}, {{'product_id': 'ABC1234', 'quantity': 1}}]

"""

agent_response = product_finder_agent.run(prompt)

return ast.literal_eval(repair_json(agent_response))

order_requests_info = order_requests_df.apply(extract_order_request_info, axis=1)

def ensure_list(val):

if isinstance(val, list):

return val

elif isinstance(val, dict):

return [val]

else:

return []

order_requests_df['order_requests_info'] = order_requests_info.apply(ensure_list)

exploded_order_requests_df = order_requests_df.explode('order_requests_info').reset_index(drop=True)

exploded_order_requests_df['product_id'] = exploded_order_requests_df['order_requests_info'].apply(lambda x: x.get('product_id') if isinstance(x, dict) else None)

exploded_order_requests_df['quantity'] = exploded_order_requests_df['order_requests_info'].apply(lambda x: x.get('quantity') if isinstance(x, dict) else None)Here’s an example of the agent’s output:

╭──────────────────────────────────────────────────── New run ────────────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ │

│ Given a customer email placing a product order, extract the relevant information from it: product and quantity. │

│ The customer might mention multiple products, but we only need those for which they are explictly │

│ placing an order. │

│ │

│ │

│ Subject: Leather Wallets │

│ Message: Hi there, I want to order all the remaining LTH0976 Leather Bifold Wallets you have in stock. │

│ I'm opening up a small boutique shop and these would be perfect for my inventory. Thank you! │

│ │

│ answer should be in this format: │

│ [{'product_id': <the product ID, in this format: 'VSC6789'>,'quantity': <an integer>}\] │

│ 'quantity' should always be an integer. If needed, check the quantity in stock. │

│ If the mentioned product ID does not follow that format (ex.: it contains spaces, '-', etc.), │

│ clean it to follow that format (3 letters, 4 numbers, no other characters) │

│ │

│ │

│ │

│ Here are 2 examples of the expected output: │

│ Example 1: │

│ [{'product_id': 'LTH0976', 'quantity': 4}\] │

│ │

│ Example 2: │

│ [{'product_id': 'SFT1098', 'quantity': 3}, {'product_id': 'ABC1234', 'quantity': 1}\] │

│ │

╰─ OpenAIServerModel - gpt-4o ────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ Step 1 ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

╭─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ Calling tool: 'query_product_db' with arguments: {'query': 'LTH0976 Leather Bifold Wallet'} │

╰─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

Observations: {'ids': ||'5', '1', '21']], 'embeddings': None, 'documents': ||'Leather Bifold Wallet Accessories

Upgrade your everyday carry with our leather bifold wallet. Crafted from premium, full-grain leather, this sleek

wallet features multiple card slots, a billfold compartment, and a timeless, minimalist design. A sophisticated

choice for any occasion. All seasons', 'Sleek Wallet Accessories Keep your essentials organized and secure with our

sleek wallet. Featuring multiple card slots and a billfold compartment, this stylish wallet is both functional and

fashionable. Perfect for everyday carry. All seasons', 'Leather Backpack Bags Upgrade your daily carry with our

leather backpack. Crafted from premium leather, this stylish backpack features multiple compartments, a padded

laptop sleeve, and adjustable straps for a comfortable fit. Perfect for work, travel, or everyday use. All

seasons']], 'uris': None, 'included': |'documents', 'metadatas', 'distances'], 'data': None, 'metadatas':

||{'fall': 1, 'winter': 1, 'summer': 1, 'stock': 4, 'price': 21.0, 'category': 'Accessories', 'spring': 1,

'product_id': 'LTH0976'}, {'fall': 1, 'spring': 1, 'winter': 1, 'price': 30.0, 'category': 'Accessories', 'stock':

5, 'summer': 1, 'product_id': 'SWL2345'}, {'fall': 1, 'summer': 1, 'price': 43.99, 'product_id': 'LTH1098',

'category': 'Bags', 'stock': 7, 'spring': 1, 'winter': 1}]], 'distances': ||0.7475106716156006, 1.036144733428955,

1.1911123991012573]]}

[Step 1: Duration 3.41 seconds| Input tokens: 1,710 | Output tokens: 23]

━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━ Step 2 ━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━━

╭─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ Calling tool: 'final_answer' with arguments: {'answer': "[{'product_id': 'LTH0976', 'quantity': 4}]"} │

╰─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯We can see it using the query_product_db tool and reflecting on its output (for example, if the requested quantity is in stock).

Process order

With the structured order information in hands, we can process those orders:

products = products_df.set_index('product_id').copy()

def process_order_requests(exploded_order_requests_df):

order_lines = []

for _, row in exploded_order_requests_df.iterrows():

email_id = row['email_id']

product_id = row['product_id']

quantity = row['quantity']

if product_id in products.index:

available_stock = products.at[product_id, 'stock']

if available_stock >= quantity:

status = 'created'

products.at[product_id, 'stock'] -= quantity

else:

status = 'out of stock'

else:

status = 'out of stock'

order_lines.append({

'email ID': email_id,

'product ID': product_id,

'quantity': quantity,

'status': status

})

return pd.DataFrame(order_lines), products.reset_index()

order_status_df, updated_products_df = process_order_requests(exploded_order_requests_df)And, finally, use an LLM to generate a human-like response: confirm or explain stock issues, suggest alternatives.

def write_order_request_response(message, order_status):

system_prompt = f"""

A customer has requested to place an order for a product.

Write a response to them, stating if the order was created or not,

and reinforcing the product and the quantity ordered.

If it was out of stock, explain it to them.

Make the email tone professional, yet friendly. You should sound human so,

if the customer mentions something in their email that's worth referring to, do it.

Do not add any other text, such as email subject or placeholders, just a clean email body.

Here are 2 examples of the expected reply:

Example 1:

'Hi there,

Thank you for reaching out and considering our LTH0976 Leather Bifold Wallets for your new boutique shop.

We’re thrilled to hear about your exciting venture!

Unfortunately, the LTH0976 Leather Bifold Wallets are currently out of stock.

We sincerely apologize for any inconvenience this may cause.

Please let us know if there’s anything else we can assist you with or if you’d like to explore alternative products that might suit your boutique.

Best,

Customer Support'

Example 2:

'Hi,

Thank you for reaching out and sharing your love for tote bags!

It sounds like you have quite the collection!

I'm pleased to inform you that your order for the VBT2345 Vibrant Tote Bag has been successfully created.

We have processed your request for 1 unit, and it will be on its way to you shortly.

If you have any further questions or need assistance, feel free to reach out.

Best,

Customer Support'

"""

user_prompt = f"""

Here's the original message: {message}

And here's the order status: {order_status}"""

return call_llm(system_prompt,user_prompt).get("ai_response")

def generate_order_response_record(row):

email_id = row["email ID"]

message = {"message": row["message"]}

order_status = order_status_df[order_status_df["email ID"] == email_id][["product ID", "quantity", "status"]]

status_dict = order_status.to_dict(orient="records")

response = write_order_request_response(message, status_dict)

return pd.Series({"email ID": email_id, "response": response})

order_response_df = order_requests_df.apply(generate_order_response_record, axis=1)5. Respond to product inquiries with RAG

Responding product inquiries requires our agent, for each email, to:

- Use the embedded vector store to find relevant products

- Build a compact, informative reply using only the top matches

We can do that by giving the specific instructions to our agent, and explaining how they can use the product search to do their task:

inquiries_df = email_classification_df[email_classification_df["category"]=="customer_inquiry"]

inquiries_df = inquiries_df.merge(emails_df, left_on="email ID", right_on="email_id")

def answer_product_inquiry(inquiry):

prompt = f"""

Your task is to answer a customer inquiry about one or multiple products.

You should:

1. Find the product(s) the customer refers to. This might be a specific product, or a general type of product.

For example, they might ask about a specific product id, or just a winter coat.

You can query the product catalog to find relevant information.

It's up to you to understand what's the best strategy to find that product information.

Be careful: the customer might mention other products that do not relate to their inquiry.

Your job is to understand precisely the type of request they are making, and only query the database

for the specific inquiry. If they mention a specific product id or type, but are not asking about those

directly, you shouldn't look them up. Just look up information that will answer their inquiry.

2. Once you have the product information, write a response email to the customer.

Make the email tone professional, yet friendly. You should sound human so,

if the customer mentions something in their email that's worth referring to, do it.

Do not add any other text, such as email subject or placeholders, just a clean email body.

Always sign as 'Customer Support'

Here's an example of the expected reply:

'Hi David,

Thank you for reaching out!

Both the LTH1098 Leather Backpack and the Leather Tote are great choices for work, but here are a few key differences:

- Organization: The Backpack has more built-in compartments, including a padded laptop sleeve and multiple compartments, which make it ideal for organizing documents and electronics.

- The Tote also offers a spacious interior and multiple pockets, but it’s slightly more open and less structured inside—great for quick access, but with fewer separate sections.

If your priority is organization and carrying a laptop securely, the LTH1098 Backpack would be the better fit.

Please let us know if there’s anything else we can assist you with, or if you'd like to place an order.

Best,

Customer Support'

Here's the user's inquiry:

Subject: {inquiry["subject"]}

Message: {inquiry["message"]}

"""

agent_response = product_finder_agent.run(prompt)

return agent_response

inquiries_df["response"] = inquiries_df.apply(answer_product_inquiry, axis=1)

inquiry_response_df = inquiries_df[["email ID","response"]]Reflection and improvements

Our approach doesn’t rely blindly on the agent: it leverages a hybrid approach:

- simple Python logic + LLM calls when that’s enough

- smolagents where sequential decision-making is needed (ex.: multi-step querying)

For production, we would definitely need a fallback to human option, monitoring, and an evaluation dataset, to assess our agent’s performance.

Overall, I think the smolagents framework provides a lot of flexibility, opening up many possibilities.